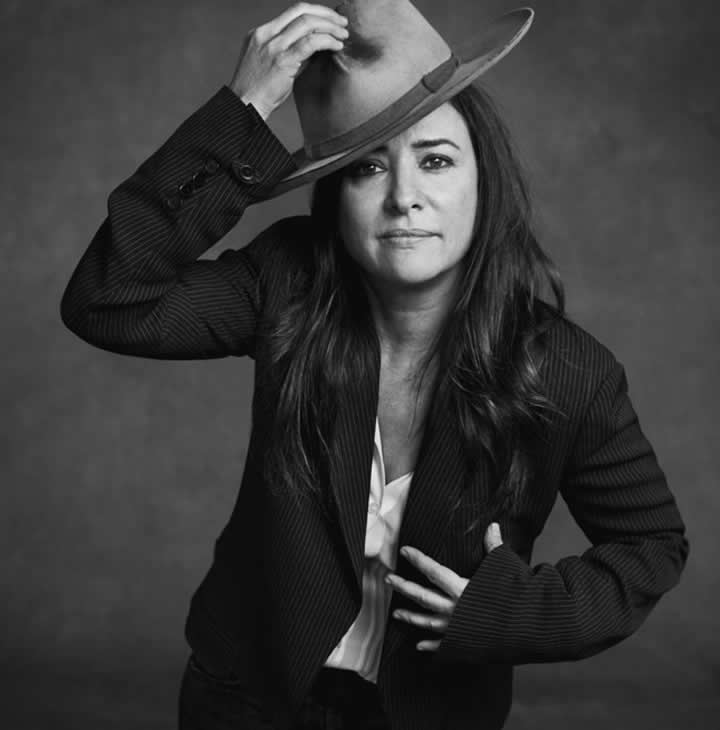

One of my favorite people on the planet is Pamela Adlon. Not only is she a brilliant actress, writer, director, producer as evidenced by her hit FX show, Better Things, for which she’s been Emmy nominated for Best Actress in a Comedy the last two years, and not only is she my favorite animated voice of all time, Bobby Hill on King of the Hill, she practically grew up in my house. She was my art assistant when she was 18, schlepping cans of paint behind me while I did tons of music videos. We’ve palled around throughout the years and she’s one of my favorite friends ever, to the point where when I get tired while hosting my parties – my favorite thing that I do – she takes over on mic and runs them for me. Anyway, there’s a great piece on her in this week‘s New Yorker, with a couple quotes by me, so check it out:

Pamela Adlon, The TV Auteur Hiding In Plain Sight

After decades on the fringes of Hollywood, the showrunner, writer, and actor talks about “Better Things,” sudden success, and her relationship with Louis C.K.

Each day, on the set of her show “Better Things,” the director and actor Pamela Adlon retreats to a small room while the cast and crew eat lunch. She turns off the lights, shuts down her phone, removes her pants and her bra, and lies face down on a couch. Often, she falls asleep. Adlon is a single mother of three daughters, as well as one of the few showrunners who direct, produce, write, and star in their own series. This makeshift sensory-deprivation room is often the only opportunity she has to generate new ideas.

One afternoon in September, during the filming of the show’s third season, Adlon was directing a scene in which her character’s increasingly absent-minded mother, Phyllis, who lives next door (as Adlon’s mother does in real life), barges into her kitchen. Adlon’s character, Sam Fox, is hanging out with her brother and a couple of friends, cooking a meal. After a take, Adlon, who likes to describe her show as “handmade,” darted behind the director’s monitor to review the footage. The cast broke for lunch, and she retreated to her chamber of solitude.

Adlon, who is five feet one inch, hunches constantly. She loves to call people “bro” and has the energy of a hyperactive teen-ager, but she also has a tendency to lumber about, brows furrowed. She looks prepubescent one moment and geriatric the next, and that makes it difficult to guess her age, which is fifty-two. She likes to come up behind her cast and crew, reach up, grab them by the shoulders, and march them over to whatever she wishes to show them. She emerged from her break and took Celia Imrie, who plays Phyllis, aside. She had decided that she wanted Phyllis, whose cognitive abilities have gradually flagged over the course of the series, not to recognize one of the friends, Rich, played by Diedrich Bader. Instead, she would think he was “a handsome, sexy man” to flirt with, Adlon said. “Even though he’s gay.”

After the next take, Bader left the set, appearing stricken. In 2017, his father died, after struggling with Alzheimer’s disease. “Alzheimer’s patients are trying to prove, like drunks, that they’re fine,” Bader said. “Before, it was a light, frothy scene about the mom not liking the risotto. And then she sprang this on me and didn’t tell me she was going to change the way she did it. This show, it’s a fluid thing.”

Adlon, however, felt that she had crossed a tonal boundary that didn’t suit the show. “It was very intense,” she told me the next day. “Now we’re getting tragic. And I always have to remember that my show is a comedy.”

“Better Things,” which airs on FX, is concerned above all with realism. “Smaller is better,” Adlon said. The show is loosely the story of a middle-aged single mother of three daughters who is also a working actor. Like Adlon, Sam is not starved for roles, but casting directors are not chasing after her, either. Sam is lewd and indelicate, but the show has a gentle way of exploring how a single mother in the entertainment industry must juggle her friends, her aging mother, her work, her shoddy romantic prospects, and the needs of her precocious, headstrong children. It is a sitcom in the lineage of shows such as “Girls” and “Insecure”—and “Louie,” which Adlon co-wrote and guest-starred on. It expresses a character-driven point of view rather than following a narrative arc. Many such shows land on unsettling or unresolved notes to affirm their commitment to truth. Adlon, though, is not afraid to make feel-good television. “It always feels like these are real choices being made, and it is, at the end of the day, a very life-affirming, heartwarming show,” Dan Cohen, one of the executive producers of the Netflix series “Stranger Things,” told me. “The show isn’t made with a grudge.”

“She did something that every writer is supposed to do, but they never actually do, which is write the show that only she could write,” Tom Kapinos, the creator of “Californication,” said. In 2007, he cast Adlon in the pilot of that show as Marcy, a foulmouthed aesthetician. Kapinos had no long-term plans for the role of Marcy, but he admired Adlon’s unflinching capacity for raunch and kept her on as a permanent cast member. (He said she became his “gutter muse.”)